BOOK REVIEW: THE POLITICS OF RESENTMENT: RURAL CONSCIOUSNESS IN WISCONSIN AND THE RISE OF SCOTT WALKER

BY KATHERINE J CRAMER

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, PP. 256

Katherine J. Cramer’s The Politics of Resentment is the indispensable book to explain Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 election. Cramer, a political ethnographer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, performed a statewide survey of Wisconsin in 2007 and 2008, prior to the fractious recall attempt on Governor Scott Walker. Cramer’s field work suggests that the prominent divide, at least in Wisconsin, is between rural and urban residents. Rural folk, she gathers, view the world through the lens of place and class. Motivated by distinct values and lifestyles, as well as economic hardship, these people have a fundamentally distrustful view of government and the public sector.

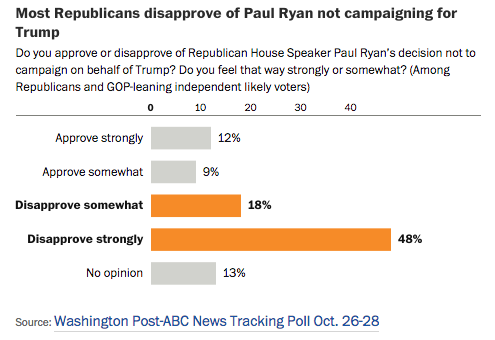

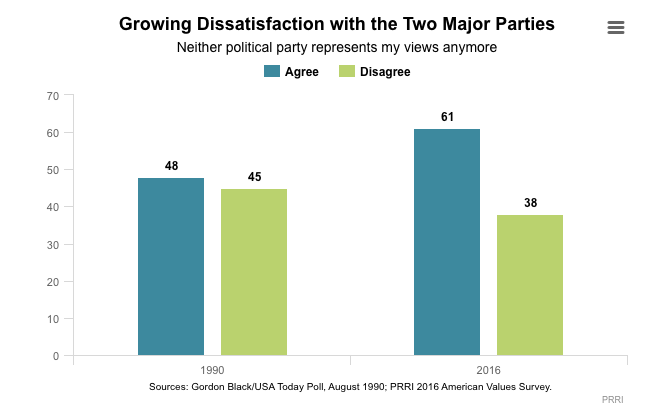

Illuminating and eerily prophetic, Cramer’s findings provide greater insight into Trump’s success. Trump exceeded expectations among blue-collar working-class voters, and his performance in rural areas exceeded that of previous Republican nominees. Cramer, who interprets her findings within a strictly state setting, does not extrapolate her conclusions to divine a national mood. Rather, she finds that, at least in Wisconsin, rural voters exhibited resentment towards public officials, who they viewed as wasteful and unproductive, and aversion to elitism. This “rural consciousness,” Cramer writes, is also shaped by concerns of economic injustice. Rural folk were angered by the possibility that their tax dollars, funneled through a burgeoning bureaucratic apparatus, were not making their way back to rural areas.

Cramer identifies three overarching elements of rural consciousness: the belief, well-founded or not, that rural areas were getting ignored by decision makers in major metropolitan centers; that they were not receiving their fair share of public spending; and that urban lawmakers and public officials had no insight into the values and lifestyles of rural people. This rural-urban dichotomy features prominently in Cramer’s findings; in fact, she concludes that it has a more binding effect on voting preferences than political partisanship. Class and location matters, she argues, because it factors into the identities of rural voters.

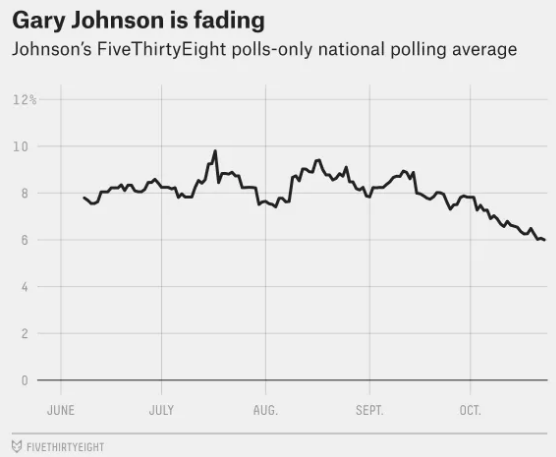

Cramer’s methodology- going to local coffee spots and gathering places in randomly chosen towns across Wisconsin- is entirely novel. In fact, she argues- rightly- that this type of survey approach should be more common in opinion analyses of voters. “[P]oll-based analyses of opinion ought to be accompanied not just by focus groups or in-depth interviews by also by listening methods that expose us to the conversations and contexts of everyday life.” Perhaps this would have been a useful corrective for the presidential polls, which grossly underestimated Trump’s performance. “We would do well to acknowledge that sometimes there is no substitute for sitting down with people and listening to their perspectives in order to measure what those perspectives are,” she advises.

The Politics of Resentment is the indispensable, must-read study of how Trump, champion of the rural and working-class, captured the presidency. Cramer’s entirely novel field survey approach, which provides a closer and more personal window into voter sentiment than traditional polling, is a whiff of fresh air amidst the statistical noise of political polling. Her conclusions should be especially worrying to governmental fixtures and establishmentarians: rural voters, animated by class and geographical setting, resent the dismissive attitudes of political elites toward their economic and cultural conditions. While Cramer might have been better to elaborate on the national implications of her findings, her insights help those baffled by the meteoric success of President-elect Donald Trump.